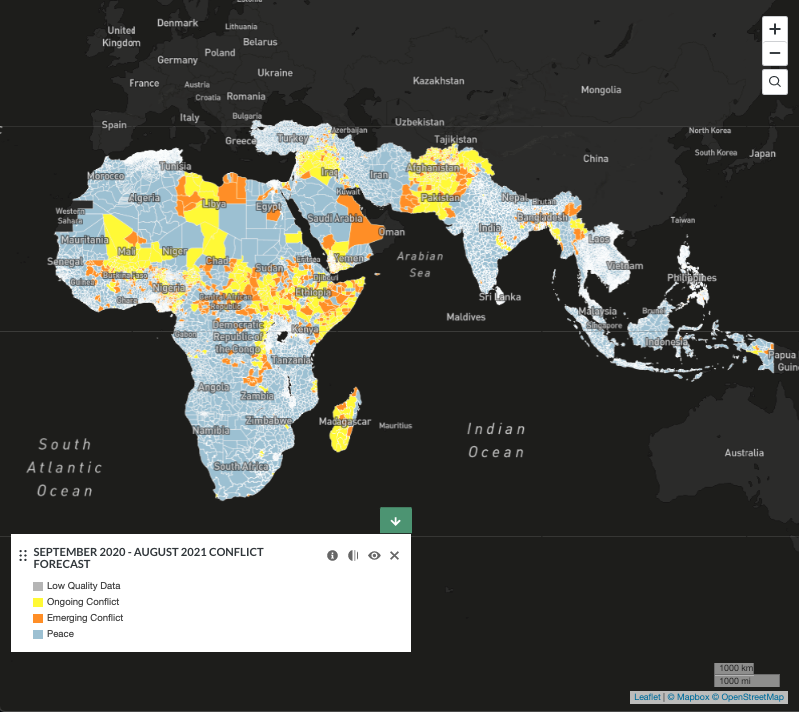

WPS Global Early Warning Tool September 2020 Quarterly Update

Global Early Warning Tool September 2020 Quarterly Forecast

POTENTIAL HOTSPOTS

This Quarterly Update flags potential hotspots in Kenya, South Sudan, Zimbabwe, Iraq, Iran-Afghanistan border regions, and Bangladesh.

East African Floods

Six million East Africans have been impacted by floods in 2020. The countries most heavily impacted include Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and South Sudan. The WPS Global Early Warning Tool predicts emerging and ongoing conflict in all these countries over the next 12 months. Below, we highlight the situations in Kenya and South Sudan.

Kenya

In May 2020, Kenyan officials estimated that massive flooding had impacted about 800,000 people throughout the country. According to Government Minister Eugene Wamalwa, “the floods and rising water levels in all our lakes and rivers is unprecedented and the devastation overwhelming. Lake Victoria last reached these levels in the 1950s and Lake Naivasha last reached these levels in 1961.” The Turkwel Dam in northwest Kenya is at serious risk of overflowing due to unprecedented rainfall. This could result in the displacement of up to 300,000 people according the Turkana County Governor Josephat Nanok. This level of displacement in a conflict-prone area like the boundary between Turkana and West Pokot counties represents a potential conflict risk. Standard precipitation index 24-month anomalies have high predictive value in our machine learning model. The WPS Global Early Warning Tool predicts emerging conflict in many areas throughout the country over the next 12 months.

South Sudan

About 400,000 people have been killed and over 4 million more have been displaced through years of civil war (2013-2020) in South Sudan. The conflict formally ended in February of this year, but violence nevertheless continues. Some of this violence is occurring between sedentary farmers and migrant cattle herders who are being forced out of their traditional grazing areas by extreme weather events, among other reasons. While conflicts between farmers and herders over water and land are not new, rapidly growing populations and climate change-driven extreme weather events appear to be ratcheting up pressure on these rural communities. This year’s torrential rains and flooding have displaced over 600,000 people and threaten “catastrophic” hunger across the country. FloodList reports that “in total, 240,000 people have been displaced in Jonglei and 221,000 in Lakes. Other affected states are Upper Nile (59,000 displaced), Unity (53,000), Central Equatoria (26,000) and Western Equatoria (4,000).” The WPS Global Early Warning Tool predicts emerging or ongoing conflict throughout most of the country over the next 12 months.

Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe’s drought-related woes continue, with about 7 million people in urban and rural areas (nearly half the country) requiring humanitarian assistance. Poor economic and political conditions, together with COVID-19 are compounding drought-driven food insecurity. FEWS NET’s most recent key message update for Zimbabwe projects “stressed” or “crisis”-level food insecurity throughout most of the country for the period of October 2020-January 2021. Zimbabwe’s two largest cities, Harare and Bulawayo, have been experiencing highly curtailed access to water due to drought. Help may be on the way, however, with FEWS NET reporting that “international climate models forecast average and above-average rainfall for Zimbabwe from October to December and January to March 2021, respectively.” The WPS Global Early Warning Tool is currently predicting emerging conflict in the Harare region over the next 12 months.

Iraq

A year and a half of violent protests across southern and central Iraq culminated in the resignation of Iraq’s prime minister in late 2019. Protesters cited a lack of access to basic services, including clean water and electricity, as one of several grievances against the government. Other grievances included widespread corruption and a lack of economic opportunities, especially for young people.

Declining flows in both the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are allowing salt water from the Persian Gulf to flow upstream, ruining productive land and rendering freshwater sources undrinkable throughout much of southern Iraq. A number of factors are driving declining river flows in the Tigris-Euphrates. One major factor is the construction of dozens of dams by upstream countries, including Turkey and Iran. Water in upstream reservoirs is being siphoned off to irrigate crops, reducing flows into Iraq.

The Iraqi government is increasing pressure on Turkey to negotiate agreements on adequate flows into Iraq. The UN International Organization for Migration, meanwhile, is warning that declining flows could result in large-scale migration out of heavily impacted regions. The WPS Global Early Warning Tool predicts emerging or ongoing conflict throughout much of southern and central Iraq over the next 12 months.

Iran-Afghanistan (Helmand River border regions)

As we reported in our last quarterly report, relations between Iran and Afghanistan — where a significant share of Iran’s water resources originates — have deteriorated as Afghanistan’s Kamal Khan Dam nears completion this year. This dam along the Helmand River — Afghanistan’s water lifeline — is expected to help irrigate hundreds of thousands of hectares of Afghan farmland and generate eight megawatts of electricity for Nimroz Province. But Afghan leaders increasingly fear Iranian interventions against the dam, which is intended to improve water security in western Afghanistan but at a likely detrimental cost to downstream Iran.

As the inauguration date (~December 2020) for the Kamal Khan Dam draws near, the rhetoric on the Afghan side is heating up, with President Ashraf Ghani vowing that the days of Iran siphoning off free water from Afghanistan are numbered. Tensions between Iran and Afghanistan in the Harirud river basin are running equally high, as the Pashdan Dam moves towards completion near the end of 2021. Many media sources report that the Iranian government has been conspiring with the Taliban to physically sabotage dam construction efforts in Afghanistan. Afghan authorities also accuse Iran of using deep wells along three rivers in the border region — the Helmand, the Farah Rud, and the Harirud — to illegally siphon off water. These accusations, which remain unproven, are contributing to increasing tensions between the countries, especially in the border regions. The WPS Global Early Warning Tool predicts emerging conflict in the Helmand River border regions over the next 12 months.[1]

Bangladesh

One third of the country had been inundated by monsoon rains as of August 2020, when Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina declared: “the heaviest rains in almost a decade … have still not abated. More than 1.5 million Bangladeshis are displaced; tens of thousands of hectares of paddy fields have been washed away. Millions of my compatriots will need food aid this year.” This disaster came on the heels of Tropical Cyclone Amphan, a category 5 “super cyclone” that made landfall on May 20, 2020. All this has taken place while the country battles COVID-19. Bangladesh, a country of 165 million people, has been experiencing more severe and more frequent flooding along the Brahmaputra River as a result of more intense rainfall, which is projected to continue worsening as a result of climate change. Standard precipitation index 24-month anomalies have high predictive value in our machine-learning model. Sea level rise will also gradually submerge large swaths of this low-lying country. The WPS Global Early Warning Tool predicts emerging or ongoing conflict throughout much of the country over the next 12 months.

ABOUT WPS AND ITS QUARTERLY UPDATES

Water, Peace and Security (WPS) Partnership. The WPS Partnership offers a platform where actors from national governments of developing countries and the global development, diplomacy, defense, and disaster relief sectors can identify potential water-related conflict hotspots before violence erupts, begin to understand the local context, prioritize opportunities for water interventions, and undertake capacity development and dialogue activities.

The Global Early Warning Tool. Our Global Early Warning Tool provides the initial step in a multi-step process, employing machine-learning to predict conflict over the coming 12 months in Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia. So far it has captured 86% of future conflicts, successfully forecasting more than 9 in 10 “ongoing conflicts” and 6 in 10 “emerging conflicts”.[2]

Quarterly Updates. We are publishing Quarterly Updates to accompany our updated maps. These Quarterly Updates flag some of the hotspot areas we are tracking and describe what journalists and other actors are seeing on the ground. While we are primarily concerned with water- and climate-related conflict, the tool is designed to forecast any type of violent conflict (and can therefore be used by a variety of users interested in conflict).

Our multistep process. Early warning is very important, especially given limits to the number of problems that national and international actors can track and address at one time. Our Global Early Warning Tool ensures that emerging conflicts can get the attention they need, early enough that potential risks can still be mitigated. Our regional- and local-level tools then support the next steps in the process and can be used to verify (or disprove) global model predictions, better understand regional and local conflict dynamics, and begin to identify opportunities for mitigating risk. WPS partners offer training and capacity development to global-, national-, and local-level actors to help them better manage risks. We can also help build constructive dialogues among parties to disputes (and other key stakeholders) that can engender water-related cooperation, peacebuilding, and design of conflict-sensitive interventions.

[1] Our machine learning model does not (yet) pick up relationships between administrative units, be they intra- or inter-national. So, while it may be tempting to say we are picking up the possibility of an international conflict, at this point we cannot say this.

[2] The trade-off for this high recall is low precision for emerging conflicts. Around 80% of all emerging conflict forecasts represent false positives, that is, instances where conflict was forecast but did not actually occur. Ongoing conflicts are much easier to accurately predict and have both high recall and high precision (<1% were false positives). We continue to work on improving the early warning model and expect that future versions will be able to better predict conflict.